I haven’t posted in a while; work and life has taken me in slightly different directions as I grapple with the potential of machine learning (less grapple, more flounder adjacent to people who know things). That research has not quite coalesced into coherency yet. So, what I’m posting today is probably the last bit of work that came out of the Provisional Semantics project (post-project stuff has a loooong-tail) with my partner in crime, the very excellent Anjalie Dalal-Clayton.

Finally getting round to putting this post up is prompted by a day long workshop looking at the (UK) Museums Association work into so called decolonisation practice in museums, and thinking again about the slippery language around DEI, decolonisation, and anti-racism work in the sector, how its packaged and instrumentalised, if we are moving forward at all or just going round again. So I am putting this out there for some of the really great people we met yesterday – some in person for the first time, some new and some old connections – I hope it resonates.

As usual these are speaking notes rather than anything more worked up and they were given in slightly tricky circumstances as family and health reasons (yes covid again) meant neither Anjalie nor I could be at the event itself. The event was Towards a National Collection Conference 2023: Unlocking the Potential of Digital Collections, at the British Museum, 26 April 2023 (recordings of all the talks can be found here) and we were supposed to be speaking on an panel on “Inclusion” chaired by Laura van Broekhoven and alongside Setareh Noorani, which would have been lovely as they are both very brilliant women doing good work. Our collegue and the Transforming Collections project Principle Investigator susan pui san lok was luckily able to step in at the last minute for the panel discussion.

In this presentation we reflect critically on our involvement in the Towards a National Collection projects Provisional Semantics (2020-2022) and Transforming Collections (2022-2024). We consider: what do we mean when we talk about ‘inclusive practices’ in museums and public collections? Could our ‘inclusive’ best practice in fact be perpetuating long-standing exclusions, given the structural racism and colonial logics inherent in the broader museum project and its conventions, histories, and infrastructure? And is genuine, long-term and embedded ‘inclusion’ effectively precluded by collections-based research projects within the museum as institution?

Neither of us are specialists on the issue or practice of ‘inclusion’ in museums, and neither of the projects within TaNC that we’ve worked on directly address it. However, some of the work we’ve done could be understood in relation to ‘inclusion’. So, in this paper, we’ll pose a few questions and offer some provocations about ‘inclusive practices’ in the museum sector based on our reflections and experience.

For us, the idea of ‘inclusion’ in museum settings raises more questions than it answers. What do we actually mean by this term? What constitutes ‘inclusive’ practice’? Who or what have we not been including and why? And what exactly is it that we are trying to include people or things into?

The development of programmes and initiatives designed to bring racialised, ‘othered’ and marginalized groups of people into the museum are variously described as ‘access’, ‘engagement’, ‘outreach’ and ‘inclusion’. The first three of these terms place emphasis on encouraging non-users or non-attendees to enter and use the museum and its facilities as they are, whilst the term ‘inclusion’ suggests something more involved and potentially more impactful on the museum’s existing structures and practices. However, in our respective 20+ years of working in and around museum settings, our observation is that, generally speaking, limited accommodations are made for ‘othered’ or marginalized groups and very few ‘inclusive practices’ involve or result in embedded changes that resolve the initial causes of exclusion. How meaningful, then, can calls for inclusion and claims of ‘inclusive practice’ be in a museum sector, that by virtue of its long history, and rigid structures and modes of operation, struggles not to exclude in the first place?

Thanks to the Towards a National Collection programme, we’ve had the opportunity to test out a range of approaches to co-producing collections information, as part of the foundation project Provisional Semantics, and also, to examine racialised exclusion in collecting, interpretation and display practices in the discovery project, Transforming Collections. Although we wouldn’t define either project as being actively ‘inclusive’, some of the work can be understood under the umbrella of inclusive practice as currently conceived in the museum sector.

In this presentation, we’ll briefly set out the approaches we employed in the three cases studies that comprised the Provisional Semantics project, explaining the issues at hand, how we attempted to address them, what happened and what we learned. We’ll then spend a few minutes talking about Transforming Collections, and then finally, we’ll share a few provocations, by way of conclusion, for all of us to consider in relation to the wider TaNC programme.

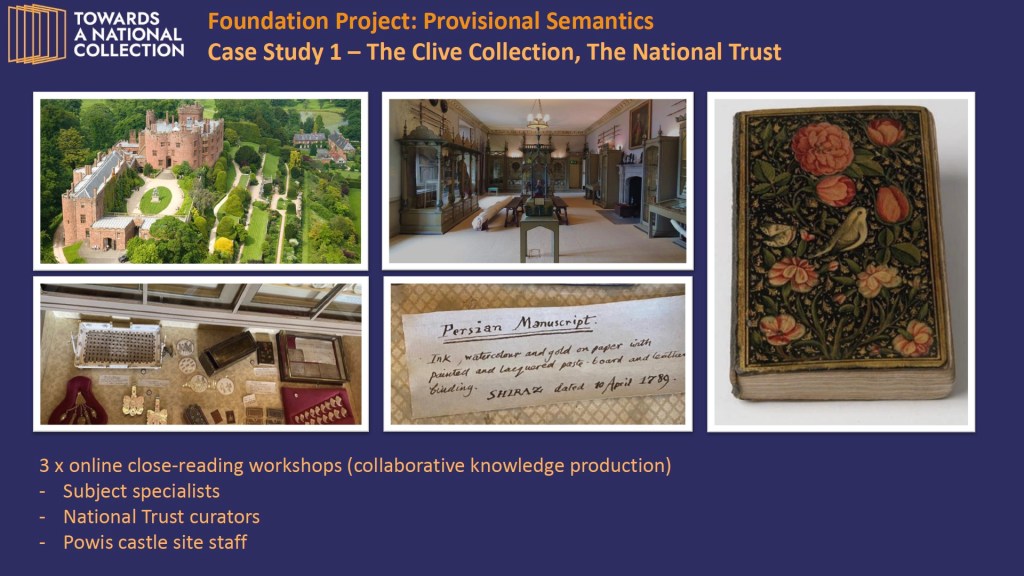

Case Study 1 – The Clive Collection, Powis Castle, National Trust

Let’s now look at the first of the three collections case studies in the Provisional Semantics project which focused on the so called ‘Clive Museum’ at Powis Castle, a National Trust property in Wales. The collection contains over a thousand artefacts from India, accumulated by Robert Clive and his family between 1744 and 1839.

Provenance information about these objects was scant or absent and their long-standing interpretation at the castle was often inaccurate and tended to romanticise the foundation of the British Empire and British conduct in India. Our objective, then, was to build knowledge around key artefacts in the collection with support from subject specialists, who could shed light on and sensitively address the corrupt and violent colonial contexts of their acquisition.

This involved three online close-reading workshops, focussing on an eighteenth-century book of poems by the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafez, a figure who is still of huge cultural, philosophical, and religious importance across the world, but whose book in the collection languished at the back of a small display case, was presented back to front, and was identified only as a “Persian Manuscript”.

The three workshops involved different stakeholder groups who each held different types of knowledge and experience and produced markedly different conversations:

The first involved specialists in Persian and South Asian literature and art history. They revealed factual and historical information about the object, as well as how to understand its history and value to multiple cultures over different time periods. Their insights exposed both our own and the Trust’s ignorance of the object and its origins, as well as highlighting the Trust’s problematic interpretations of it to date.

The second workshop involved National Trust curators who could critically reflect on the display and interpretation of the book in relation to practices and policies both within the Trust and across the wider sector. The curatorial staff were able to provide close analyses of how the language in documentation and interpretation had affected engagement and understanding of the book and the collection and were able to reflect on practical changes for updating curatorial approaches within the Trust.

The third workshop involved Powis Castle staff and volunteers who helped to us to look beyond the interpretive texts and revealed how knowledge and oft repeated family anecdotes were uncritically presented to visitors. Although some amongst this group were concerned about the veracity of these stories and expressed a desire to see new, unexpurgated interpretations of the collection within the museum, others were highly averse to ‘decolonial’ approaches to history and were defensive of long-standing narratives that are increasingly being challenged and problematised.

This case study was essentially a process of collaborative knowledge production and overall, the workshops revealed the broad-ranging and differing perspectives held on this collection. However, they highlighted the importance of addressing knowledge gaps and mitigating causes of further offence and exclusion, before embarking on engagement or inclusion activities with wider, non-academic stakeholder communities.

Case Study 2 – Imperial War Museums

The second Provisional Semantics case study focused on a collection of British official photographs held at the Imperial War Museum, or IWM. They were taken in India in 1942, covering recruitment of Indian servicemen during the Second World War. When the project began, the only source of information about the photographs was the original typed captions on the back of each image which included inaccurate and problematic information, language, and narrative framing, and had precluded their display at the IWM.

As with the National Trust case study, this was another situation where it was necessary to solicit information about the photographs from subject specialists, before any further work could be undertaken. The IWM approached three historians of the Indian experience of the Second World War, two of whom are from India.

Taking a step further than with the National Trust case study, we commissioned them to research and write about the photographs, with a view to publishing new captions and contextual essays on the IWM webpages. This allowed us to critically observe some of the challenges of co-production as an ostensible form of ‘inclusive practice’, particularly in terms of how it can be shaped in and by the museum as institution.

The brief to the subject specialists included two main challenges. The first was to identify and address both the archaic and offensive terms found in the original captions and the problematic attitudes and frameworks that informed the use of such terms. The second was not to replicate colonial tropes in the new captions. All three were able to respond to these challenges, but to varying degrees. Specifically, we observed that the specialists who were actually from India were better equipped to identify where colonial tropes resided in seemingly innocuous phrasing and descriptions, often appearing as benign in a traditionally white British setting. They were also better able to address the histories, impact and legacies of empire in India in a critical but culturally sensitive way in their new captions.

For the IWM, the act of commissioning subject-specialists not already employed or trained by the museum was viewed as a fairly radical opening out of its documentation practices, and a step towards multi-vocality. However, within the project we concluded that commissioning established military historians to produce interpretation for this particular collection of photographs was actually a rather conservative approach to ‘including other voices or perspectives’, compared to collaborating with individuals working in other disciplines, or commissioning an entirely Indian cohort of respondents, and it again demonstrates that there are numerous steps to be taken to address exclusion, before we can claim that our work is inclusive.

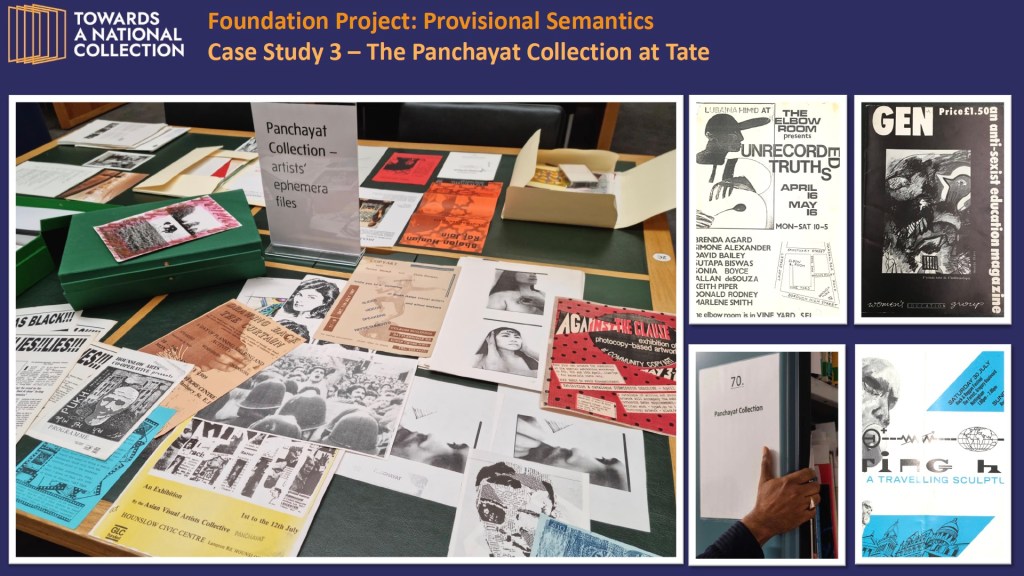

Case Study 3 – The Panchayat Collection at Tate

The Tate case study was perhaps the most obviously ‘inclusive’ in practice and execution, and was also the most involved and complex.

It focused on the Panchayat Collection, which contains publications, documents and ephemera relating to the practice and exhibition histories of artists with South Asian, Caribbean, and African heritage, living and working in Britain during the 1980s and 1990s. The collection was established and built by a group of 5 such artists, in the 1980s, calling themselves the Panchayat Arts Education Resource Unit. The collection entered the Tate Library in 2015, but had not been catalogued by the time the project started in 2020. Additionally, its ephemera and archive items were inadequately served by library cataloguing systems and current library search terms, a combination which rendered them effectively invisible.

Recognising that we had a unique opportunity to engage with the living founders, custodians and stakeholders of the collection, our objective was to develop collections knowledge of the Panchayat in close collaboration with them and to surface the challenges of doing this. The supposedly ‘inclusive approaches’ we engaged in this case study were to commission the founders and custodians to devise a range of resources to provide history and context for the formation of the collection, its role within the international art world, and to highlight the practices of artists represented in the collection. However, the importance of this case study – for the purposes of this panel – is less about its methods and outcomes than it is about the context in which the case study, and indeed the entire project, evolved.

This project sought to test co-production strategies for developing knowledge about, and descriptions and search terms for, collections that represent the histories and experiences of people of colour. So, it would’ve been appropriate for the project, its questions and methods to be significantly shaped by researchers with both appropriate expertise and lived experience. This did not happen. The project’s principle questions, foci and objectives had been determined in a majority white project team. The impacts of this are too numerous and nuanced to discuss here, but needless to say, this was not a particularly ‘inclusive’ or representative start to the project.

Thinking specifically about the Tate case study, the opportunity to develop the research with the Panchayat Collection’s founders and custodians was not actually taken until several months into the project, meaning, that the shaping of the case study was not informed by the people implicated in, or represented and impacted by the project. Our failure to think and act ‘inclusively’, not only in the Tate case study, but from the very outset of the project itself, meant that our objectives and methods required constant rethinking throughout the project, that relationships with the collections’ key stakeholders were strained and in need of repair and reparation, and ultimately, that our efforts could never fully serve the requirements and expectations of the people who really mattered in the project.

It was primarily through this case study that we began to critically reflect on the ethical and practical issues of research project structures, and the complex challenges of attempting to incorporate a genuinely collaborative, multi-perspectival and open approach to working with external stakeholders in institutional practice.

On the basis of the understanding that inclusion cannot be achieved without first addressing precisely how and why exclusions are made in the first place, our current project, Transforming Collections, makes exposing the mechanisms of exclusion within collecting and documentation practices its primary focus, rather than championing inclusive practices.

Transforming Collections Project

The key questions for the project are, who in the art historical narrative and by extension the digital cultural record, has been ignored, overlooked, or neglected; why this happens; and what can be done to change this? Our researchers are engaged in a range of case studies that seek to surface suppressed histories, amplify marginalised voices and re-evaluate artists and artworks ignored or side-lined by dominant narratives, as well as how machine learning can support these efforts. We hope that academics examining the technological challenges of joining up multiple varied collections, both within and beyond the TaNC programme, will find use and value in the project’s interrogation of bias within the language used by museums and heritage organisations to catalogue and interpret their collection

Since Transforming Collections is still in process, it’s difficult to draw out conclusions from the project that respond directly to topic of this panel. So instead, we conclude with some final thoughts on project working and how we feel future projects can be conceived, devised, and implemented in order to address the issues of exclusion and inclusion in a more embedded, sustainable and impactful way.

Our experiences have revealed how far entrenched, often hidden, practices of exclusion are not really addressed by mainstream inclusion rhetoric, and our projects have attempted to recognise and address exclusion before the steps towards being inclusive can be taken.

In cases where collections and individuals have been historically marginalised, a huge degree of reparative sensitivity is required by the institutions that hold those collections. However, our experience has been that the project format doesn’t serve relationships between stakeholders and institutions well. We have found that trying to build trust within a time and scope restricted research project is difficult, especially in an environment where institutional reparations for past erasures and exclusions are needed.

We’ve observed how co-production of collections information easily becomes extractive when carried out in an institutional context, even when employing methods that are positioned as solutions to racial bias and exclusion. For example, recording personal accounts, documenting artistic practices, determining contractual obligations, negotiating intellectual property rights, and agreeing on use, are typically imbalanced in favour of the institution, and not the individuals the project seeks to ‘include.’ These aspects of co-production, as well as the relationship between cost and benefit to those positioned outside or adjacent to the institution, as both subject and object in the research process, require significant consideration and navigation. Project budgets, timescales and use of institutional contracts can impact negatively on the formation of ethical and equitable partnerships and collaborations.

It’s crucial, then, to build in time and resources to develop networks and relationships of trust with the appropriate prospective researchers and participants. This needs to happen during bid development and not reactively during the course of the project. Further, at the other end of the project Gantt chart, it’s crucial to look at project legacies. That is, how people and relationships will be supported by the institution after project end, how material will be accessed and used, and how that access will be maintained.

Investment and focus to co-produce collections knowledge ethically and equitably is crucial. But just as important is dedicated time and space to set down this knowledge in the catalogue record. This vital work has been sidelined in favour of digitisation that privileges images, and limited metadata for some time now. In our view, cataloguing should be regarded as a core output for funded collections-based projects. Without it, the actual and long-term impact of further collections research and the legacy of projects such as those within TaNC is significantly curtailed. Additionally, it is the forgotten, erased, marginalised or underrepresented objects that should be prioritized in careful and collaborative cataloguing, rather than the traditionally recognised ‘star’ objects or collection highlights.

Finally, to the make-up of project teams. The legacies of colonialism and imperialism, and present-day structural racism and bias, are woven insidiously through every aspect of contemporary life. All projects, no matter their topic, will be impacted by these factors in some way, even if it’s not immediately apparent. To be able to identify and address where and how this occurs, it is not simply desirable, but essential, to put in place a diverse research team. The team should not only be representative of the topics being investigated, but it should also have expertise in the socio-political sensitivities at play. Lived experience of racialisation and marginalisation, within a research team, increases its ability to identify where and how structural racism and imperial thinking impact the research. It can also potentially increase a project’s ability to mitigate against the unwitting perpetuation of these systems of oppression within the project itself. It is our contention that inclusion, or rather, addressing exclusion, is only possible with diverse and representative research teams as well as genuine power sharing and ethical co-production, established from the conception of research projects, and further, that this should be a required metric for funding approvals.

Leave a comment